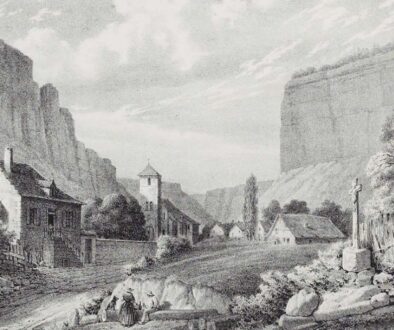

Caves vigneronnes à Baume-les-Messieurs

In the steep, limestone-strewn hills of Baume-les-Messieurs, old farmsteads and vineyard structures blend seamlessly into the landscape.

At first glance, a low stone doorway tucked into a roadside building might look like a barn — but in this corner of the Jura, it could very well be the entrance to a centuries-old wine cellar.

How to Tell a Wine Cellar from a Barn Entrance in Baume-les-Messieurs

1. Location & Orientation

Wine Cellar: Often built into the slope of a hill or mountain, facing north or northeast to maintain cool, stable temperatures. You’ll find them near former vineyard plots or old farmhouses with terraced land above.

Barn: Usually sits on flatter ground or at the base of a slope, oriented for easy access by cart or livestock. Often paired with a visible courtyard or animal pens.

2. Doorway Architecture

Wine Cellar: Typically has a small, arched or rectangular stone doorway, sometimes with a heavy wooden or iron-reinforced door. Look for a low lintel — often just 1.5 to 1.8 meters high — designed to limit air exchange and maintain humidity, and descending steps.

Barn: Wider, taller entrances (often 2+ meters high) to accommodate wagons, animals, or hay carts. May feature wooden double doors, sometimes with iron hinges or decorative wrought iron.

3. Ventilation & Drainage

Wine Cellar: May have small, high-set ventilation slits or “breathing holes” near the ceiling — essential for air circulation without temperature swings. Often includes a shallow drainage channel at the threshold to manage condensation or seepage.

Barn: Ventilation is more open — large gaps under doors, louvered windows, or roof vents. Drainage is designed for manure and rain runoff, not humidity control.

4. Surrounding Features

Wine Cellar: Often surrounded by stone retaining walls or terraces — remnants of former vineyards. You may spot old stone troughs (for rinsing grapes) or embedded metal rings (for securing barrels).

Barn: Surrounded by paddocks, feeding troughs, or manure piles. Look for hitching posts, hayloft openings, or animal stalls visible from the outside.

5. Signs of Use

Wine Cellar: May have faint wine stains on the threshold, old barrel staves leaning nearby, or a lingering earthy, musty aroma (especially after rain). Some still have original stone wine presses or fermentation tanks inside.

Barn: Smells of hay, animals, or damp straw. You might see tools like pitchforks, milking stools, or rusted plows nearby.

Ask Locals

In Baume-les-Messieurs, many cellars are still privately owned and not marked on maps. If you’re exploring, don’t hesitate to ask residents — they often know which stone door leads to wine history and which leads to cows.

Many wine cellars in Baume-les-Messieurs are not open to the public — always respect private property and closed doors.

This subtle distinction reflects the village’s layered past: where vines once grew, cows now graze — but the stone doorways still whisper of wine.

From Vine to Pasture: How Phylloxera Reshaped Wine and Life in Baume-les-Messieurs, Jura

Nestled in the limestone folds of the Jura Mountains, the village of Baume-les-Messieurs once thrived as a modest but proud wine-producing enclave. Its steep slopes, sheltered valleys, and monastic roots made it ideal for viticulture — until the 19th century, when a tiny insect changed everything.

Vineyards Rooted in Monastic Tradition

Winegrowing in Baume-les-Messieurs dates back to at least the 7th century, when the Abbey of Baume-les-Messieurs — a spiritual and agricultural center — began cultivating vines on its surrounding slopes. The monks, skilled in land stewardship, planted varieties suited to the cool, Jurassic terroir: Savagnin, Poulsard, and Trousseau. Their wines, though modest in volume, were integral to local life — used in liturgy, trade, and daily sustenance.

By the 18th and early 19th centuries, vineyards dotted the hillsides, tended by generations of small-scale farmers who balanced viticulture with livestock and grain. But this quiet rhythm would soon be shattered.

The Phylloxera Catastrophe

In the 1870s, phylloxera — a microscopic aphid native to North America — reached the Jura. Carried unknowingly on imported American rootstock, the pest attacked the roots of European Vitis vinifera vines, causing them to wither and die. Unlike in regions like Bordeaux or Burgundy, where replanting on resistant American rootstock became the norm, many Jura communities — including Baume-les-Messieurs — lacked the capital, infrastructure, or technical knowledge to respond effectively.

The devastation was swift and total. Vineyards that had stood for centuries were abandoned. Families who had relied on wine for generations faced economic ruin.

The Rise of Dairy Farming

With vines gone and no clear path to replant, many farmers in Baume-les-Messieurs turned to what the land could still support: dairy. The lush pastures, fed by the Doubs River and the region’s abundant rainfall, proved ideal for raising cattle. Cheese — particularly Comté, the region’s famed aged mountain cheese — became the new economic backbone.

Dairy farming offered stability where viticulture had failed. It required less upfront investment, aligned with existing agricultural practices, and tapped into growing regional and national markets. By the early 20th century, Baume-les-Messieurs had become more known for its cows and cheese than its wine.

Modern Revival and Tourism

It wasn’t until the late 20th and early 21st centuries that wine began to return to Baume-les-Messieurs — not as a mass industry, but as a craft.

A handful of passionate vignerons, often working in tiny plots or on terraces reclaimed from pasture, began replanting with grafted vines, embracing organic and biodynamic methods.

Today, their wines — often made in minute quantities — are celebrated for their purity, minerality, and connection to place.

The story of Baume-les-Messieurs is one of resilience. Phylloxera didn’t just destroy vines — it reshaped livelihoods, landscapes, and local identity. Yet, in the quiet revival of its vineyards, the village honors both its past and its capacity to adapt.

Wine here is not just a product — it’s a continuation of a centuries-old dialogue between land, labor, and time.